Beijing is best known as China’s capital city, an expanding modern city of high rises and traffic-clogged ring roads, but Beijing municipality covers an area half the size of Belgium: it has a large rural hinterland of small towns and mountain villages. Each winter, pollution from domestic coal burning in the outlying areas takes a heavy toll on the city.

Household use of coal for heat and cooking accounts for 18% of all energy use in Beijing municipality – but 50% of black carbon (BC) and 69% of organic carbon (OC), according to a study by researchers from Canada, the US, UK, and the State Key Joint Laboratory of Environment Simulation and Pollution Control at Peking University’s College of Environmental Sciences and Engineering, that was published in May in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America (PNAS). Both black and organic carbon are types of soot, and of the tiny PM2.5 particles that can enter human tissue and the bloodstream when inhaled.

Government priority

As measures to control air pollution have removed most industrial polluters like steel works from Beijing city, dealing with domestic soot has moved up the agenda. “Strengthening control of air pollution from household coal burning and providing replacement fuels” topped a list of pollution control measures put forward at a January meeting on air pollution in Beijing chaired by Zhang Gaoli, vice premier of the State Council.

The Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region becomes a smog zone during winter, with PM2.5 levels six times those regarded as safe by the World Health Organisation (WHO). In extreme cases levels rise to “instrument busting” heights.

There are different types of PM2.5 pollution, with different health consequences. Research has shown that black carbon, created when fossil fuels or biomass is incompletely combusted, has a greater impact on health than other particulates.

Big impact of small stoves

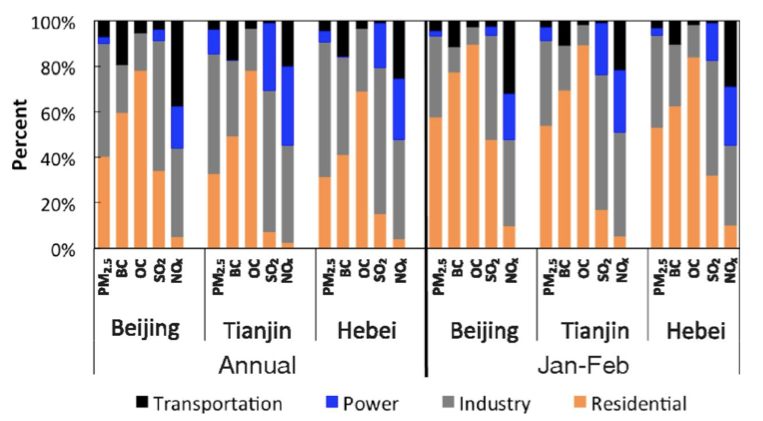

It is not widely understood that more black carbon is given off by domestic coal burning than by the transportation and electricity generation sectors combined. In winter, household emissions surpass those of industry as a whole.

Relative contributions of the transport, power, industry, and residential sectors to PM2.5, BC, OC, SO2, and NOx emissions in Beijing, Tianjin, and Hebei in 2010 and in January and February of 2010 alone. Zhu Tong et al, Air pollutant emissions from Chinese households.

Controlling household coal use would significantly improve air quality in Beijing and Tianjin and Hebei province, surrounding the two megacities, the PNAS report found. Full control of household coal burning would reduce annual average PM2.5 levels by 32%, giving greater benefits than could be produced from improvements in other sectors.

But what fuel can be used to replace coal, which is a cheap source of energy for poorer, rural households?

Semi-coke briquettes, also known as “clean coal,” are currently the most popular, and controversial, substitute. The briquettes are pellets made from bituminous coal treated to stabilise or strip out the volatile compounds that cause soot and carbon emissions. They are burned primarily in small stoves and boilers.

Although the government generally favours replacing domestic coal consumption with district-wide heating systems, or gas or electric heating, rural residents tend to prefer semi-coke briquettes. They require little investment, and it is much easier to install the stoves than to lay large networks of pipes.

Price and convenience are the most important factors to them.

Semi-coke briquettes are the best solution when weighing up the balance of cost and environmental friendliness, as they are far cheaper than the alternatives and cleaner than coal, according to Ge Su, a visiting professor at Nankai University’s College of Environmental Science and Engineering.

Cleaner air, dirty water

It is wrong for anyone to look at price alone, says Jia Li of the School of Mechanical, Electronic and Control Engineering at Beijing Jiaotong University, stressing that coal has complex constituents, so simple processing will not suddenly make it a clean fuel.

It’s a view supported by Yang Fuqiang, a senior adviser with the National Resource Defense Council’s China Program.

The manufacture and use of semi-coke briquettes should be approached cautiously, he says, telling chinadialogue that wastewater produced in manufacturing the briquettes is hard to treat, and can damage local surface and ground water.

Shaanxi province is the main source of briquettes. It’s an arid region where water scarcity means pollution cannot be washed away from local soils. Yang believes that semi-coke briquettes may not be better for the environment once the whole product cycle is considered.

Nor can the issue of greenhouse gas emissions be overlooked. According to Yang Fuqiang, the use of semi-coke briquettes will not help meet climate targets if, over the entire product cycle, more carbon dioxide is released.

Bioenergy

Another possible replacement for coal in rural areas is bioenergy, a clean and carbon neutral source of energy. The process of collecting, storing, transporting and converting raw materials into bioenergy is labour intensive – which seems to be ideal for China, which is trying to boost rural employment. It would provide energy for rural areas and any excess can be sold to the cities.

However, Wang Weiquan, deputy secretary of the Chinese Renewable Energy Industries Association, admitted that in fact popularising the use of bioenergy, such as methane, in rural areas would not be easy. First, rural households, which are numerous and widely scattered, are much harder to manage than a few large companies. Second, rural residents have low levels of environmental awareness, and will burn whatever happens to be cheap. If the government does not provide subsidies for refits or fuels, they won’t use them. But government subsidies can create reliance, problems can arise with the transfers of funds, and subsidies are not sustainable under the current economic downturn.

“So we need to see how good the government is at innovating,” said Wang Weiquan. He says finding investors to set up business-government cooperative models may be a route to both providing rural energy and meeting environmental targets.

He also said there is a greater need for indirect incentives, such as strict controls on coal. Further restricting the coal industry would give all renewables, including bioenergy, space to grow.