Environmentalists and citizens alike are questioning the official explanation for the alarmingly high concentrations of sulfur dioxide that have recently plagued Linfen, a city in northern China’s Shanxi province.

Zhang Wenqing, deputy chief of the municipal environmental protection bureau, told a local reporter early January that “70 percent of sulfur dioxide emissions come from citizens’ coal use.”

Cooking stoves are a favourite scapegoat of local Chinese governments during times of smog. Beijing authorities on January 9, advised residents not to cook when there is heavy air pollution, and in September 2016, the government of Baoding, a city near Beijing, even forbade its citizens from cooking with coal in an effort to limit smog.

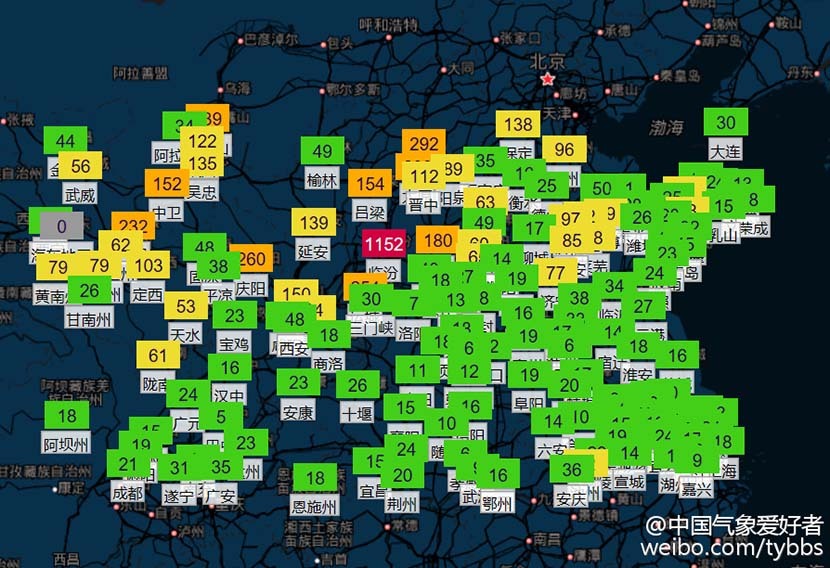

Zhang’s remarks came in response to residents expressing alarm over the city’s extremely high pollution levels. On January 4, netizen “China Weather Lover” posted on his Weibo microblog about Linfen’s sulfur dioxide levels, which are measured in micrograms per cubic metre. “Most other cities have a two-digit number, while Linfen’s is 1,152,” he wrote, attaching a screenshot of a map comparing Linfen to other cities in China.

A map shows sulfur dioxide levels across China. Levels in Linfen, Shanxi province, reached 1,152 micrograms per cubic metre on Jan. 4, 2017. @zhongguoqixiangaihaozhe from Weibo

On the afternoon of January 9, the deputy mayor of Linfen apologised to the public for recent events, according to a report posted on the city’s environmental protection bureau website.

In front of television cameras and reporters, Yan Jianguo said he accepted the recent criticism from the public and media, and outlined new policies that included improving the communication of information about air quality to citizens, increasing awareness of pollution-related health risks, and better controlling the sources of harmful pollutants.

Sulfur dioxide is a gas produced by the burning of fossil fuels such as coal and oil. According to the World Health Organization, high levels of sulfur dioxide can harm the respiratory system and are linked to upticks in hospital admissions for cardiac disease. WHO guidelines state that long-term levels should be below 20, and that people should not be exposed to concentrations exceeding 500 for more than 10 minutes.

In comparison, sulfur dioxide concentrations in Linfen were higher than 700 for hours at a time in early January, according to data from aqistudy.cn, a weather data website operated by a nongovernmental organisation. The highest recorded concentration was 1,331 on the evening of January 4.

Li Ting, a postdoctoral meteorology researcher at the Chinese Academy of Sciences, further raised awareness of the issue by posting two articles on social media warning people of the dangers of high sulfur dioxide levels. In her second post, she mentioned being frustrated after calling the Linfen environmental protection hotline.

“I can feel their arrogance during the phone calls,” Li said of the officials she spoke to. “They replied very politely but did not provide any useful information.” The post was deleted from Weibo within 12 hours but remains available on Li’s public account on messaging app WeChat.

The explanation by local official Zhang has done little to assuage the public’s concerns. “People have used coal for years and still use it every day,” wrote one user. “Why are the numbers so high this year?”

Dong Liansai, a climate and energy campaigner at environmental organisation Greenpeace East Asia, told Sixth Tone he also questions the official explanation that household coal burning was the main culprit.

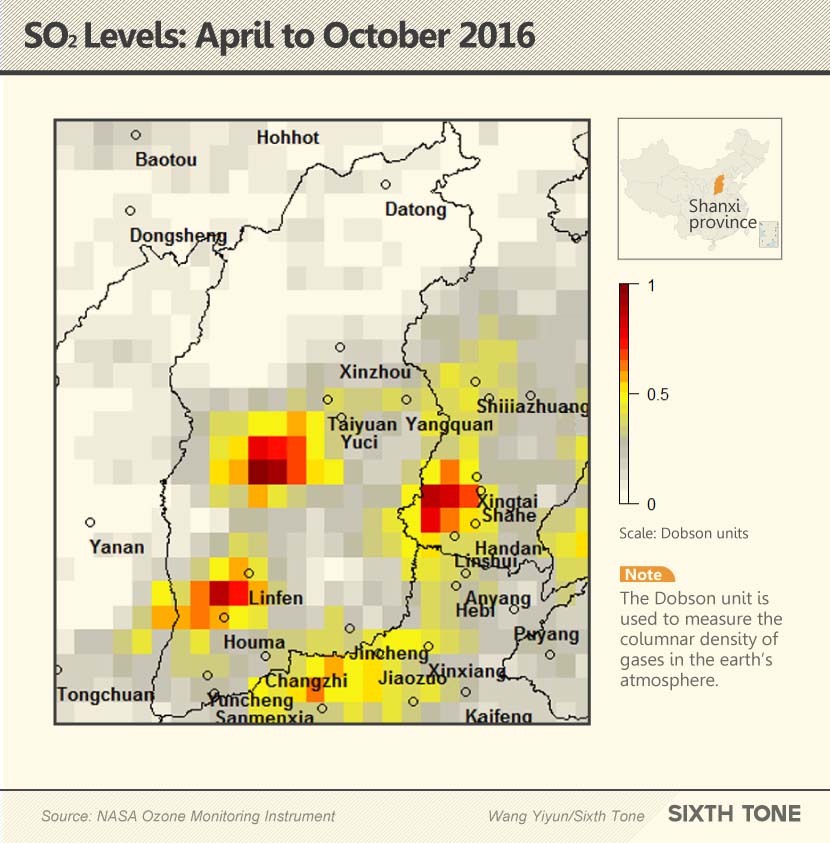

“According to Greenpeace analysis, on days outside of heating seasons, when the residential heating is unlikely to happen, Linfen is still one of the biggest hotspots of sulfur dioxide in China,” Dong told Sixth Tone. He also referred to a map from NASA showing heightened sulfur dioxide levels in the region over a seven-month period in 2016.

Ministry of Environmental Protection (MEP) statistics for Shanxi province seen by Sixth Tone also show that power stations and industries were the two main sources of sulfur dioxide emissions in 2014, at 45.6% and 32.6% respectively.

Ma Jun, founder and director of the Institute of Public and Environmental Affairs (IPE), an environment watchdog, told Sixth Tone that Zhang’s remark is hard to verify, as Linfen rarely publishes information on emissions by local businesses.

Ma said Linfen has failed to adhere to regulations published by the MEP in 2013 that require companies that are major polluters to publish their emissions data under supervision by the local government. The municipality ranked 118 out of 120 Chinese cities in IPE’s 2015-2016 Pollution Information Transparency Index.

Sulfur dioxide levels in Linfen have since declined. Dong of Greenpeace said a government emergency response has triggered a shutdown of high-emissions industries, but that these short-term measures cannot meet the long-term goal of guaranteeing clean air.

“Only by strong supervision and enhanced monitoring can the Ministry of Environment Protection end the game of cat and mouse, and put the duty of compliance back to the industry owners,” Dong said.

This article is republished from Sixth Tone