Years from now passing travellers may marvel at the grandeur and the folly of the futuristic landscape on the edges of Abu Dhabi: the barely occupied office blocks, the deserted streets, the vast tracts of undeveloped land and – most of all – the abandoned dream of a zero-carbon city.

Masdar City, when it was first conceived a decade ago, was intended to revolutionise thinking about cities and the built environment.

Now the world’s first planned sustainable city – the marquee project of the United Arab Emirates’ (UAE) plan to diversify the economy from fossil fuels – could well be the world’s first green ghost town.

As of this year – when Masdar was originally scheduled for completion – managers have given up on the original goal of building the world’s first planned zero-carbon city.

Masdar City is nowhere close to zeroing out its greenhouse gas emissions now, even at a fraction of its planned footprint. And it will not reach that goal even if the development ever gets fully built, the authorities admitted.

“We are not going to try to shoehorn renewable energy into the city just to justify a definition created within a boundary,” said Chris Wan, the design manager for Masdar City.

“As of today, it’s not a net zero future,” he said. “It’s about 50%.”

When Masdar City began, in 2006, the project was touted as a model for a green mixed-use urban landscape: a global hub for the cleantech industry, with 50,000 residents and 40,000 commuters.

Foster + Partners designed a car-free city scape, with Jetson-style driverless electric cars shuttling passengers between buildings incorporating built-in shades and kitted out with smart technologies to resist the scorching desert heat, and keep cooling costs down.

Mubadala, Abu Dhabi’s state-owned investment company, pledged financial support to the estimated US$22 billion experiment in urban design.

Ten years on, however, only a fraction of the town has been built – less than 5% of the original six square km “greenprint”, as Wan called it. The completion date has been pushed back to 2030.

The core of Masdar City is in place, anchored by the large square-ish building that is the Middle East headquarters of Siemens. A 45-metre Teflon-coated wind tower helps channel cooling breezes down a shaded street equipped with a grocery store, bank, post office, a canteen, and a couple of coffee shops.

As many as 300 other firms such as GE’s Ecomagination and Lockheed Martin also have an official presence – though Wan acknowledged that in many cases that just amounts to a hot desk.

The International Renewable Energy Agency took over the other major building for its shimmering steel headquarters last year.

Irena chose Abu Dhabi as its base, after Masdar promised a state-of-the-art sustainable building. The six-storey headquarters uses only one-third of the energy of comparable office buildings in Abu Dhabi – thanks to air-tight insulation and high-efficiency elevators. The design rejected overhead lamps, to encourage use of natural lighting, and called for solar water heaters on the roof.

A wind tower within Masdar. The city has given up on its original aim to be net zero. Photograph: Clint McLean/Corbis

By UAE standards, both the Siemens and the Irena buildings are state-of-the-art in terms of optimising energy use – but it’s less clear how they stack up globally. The UAE uses its own ratings system which does not readily translate to more familiar green building standards.

In addition, the agency’s 90 or so staffers are the only occupants of the six-storey, 32,000m space. Fewer than 2,000 people work on the campus, according to tour guides.

Only 300 live on-site, all graduate students of the Masdar Institute of Science and Technology, who are given free tuition and accommodation.

The pioneering autonomous transport system – which was originally supposed to stretch to 100 stations – was scrapped after the first two stops.

There is a bike-sharing station – though it’s a good 10 miles away from Abu Dhabi, and there are no bike paths.

And the rationale for Masdar City – demonstrating a model of green living – has been abandoned. “The original aim was to be net zero, yes, but that was when we were looking at the city in isolation,” Wan said.

He maintained it was important to look at Masdar City within the context of the other renewable energy holdings of the parent company. Among Mubadala’s other holdings, Masdar Clean Energy is developing the Shams solar farm.

“Masdar as a family company is supply[ing] much, much more clean energy than what is being consumed in the city, for sure,” Wan said. “All I am saying is that we are not going to use a city line boundary to try to dictate what is the most cost-effective way to produce clean energy, because the money invested in Masdar City and the money invested in Shams is the same source.”

He went on: “In the bigger picture I am doing more good for the country and for planet Earth because it’s much more efficient.”

Long before the drop in oil prices, the UAE led the oil-producing Gulf countries in moving their economy away from fossil fuels.

The country’s leaders, staring at the prospect that their estimated reserves could run out in 50 years, invested in tourism, tech and renewable energy. Today about 70% of GDP comes from non-oil sectors, according to Mohammed Bin Rashid Al Maktoum, the UAE prime minister.

The country is eager to be seen as a leader in renewable energy and sustainability, convening regular leadership retreats to discuss their future beyond oil.

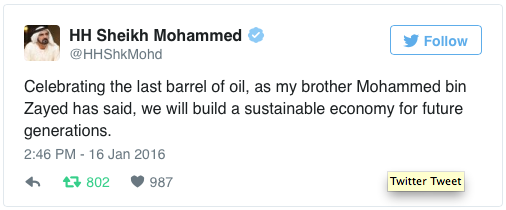

In January the country’s prime minister tweeted:

The UAE spent US$20 billon on a nuclear power plant, still under construction, projected to produce close to 25% of its electricity by 2020. The country is also building what has been billed as the world’s biggest solar farm in Dubai, and to install rooftop solar on every home in the emirate by 2030.

The first 25 families have moved into a net-zero emissions residential neighbourhood in Dubai, with plans for a solar-powered hotel and school. “Whether we are an oil state or not, we need to take care of the Earth and future generations,” said Emil Samarah, one of the developers.

With the downward pressure from oil prices, the UAE has stepped up its efforts to wean itself off oil, lifting fossil fuel subsidies and billing Emiratis – not just expatriates – for water and electricity.

But delivering on the original dream of Masdar has been elusive. Crews broke ground in 2008, but plans withered in the global economic recession which soon followed when investors put their green dreams on hold. “A lot of the people who were considering investing in Masdar City decided to take a breather,” Wan said.

Meanwhile, the jet-set transport system was overtaken by technological developments in the auto sector. The expensive purpose-built system no longer made sense in an era when zero-emission electric cars were widely available. “Five years ago it’s true that we did not perceive the speed with which the electric vehicle would be developed,” Wan said.

But he insisted that Masdar was not a total failure. “Masdar is part of an evolutionary process,” he said.

This story appeared originally on the Guardian’s website and reprinted with permission.