Hong Kong is leaky.

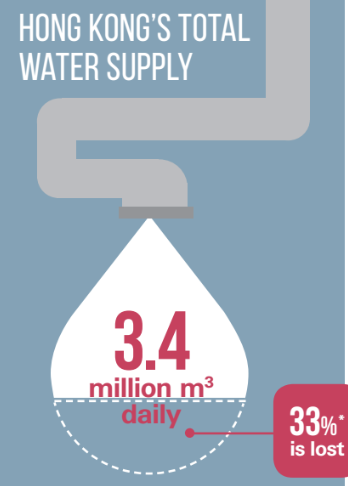

Despite being one of the world’s richest cities, it’s annual loss of water from leakage and theft is a whopping 32.5% of total production, or 321 million cubic metres (m3).

Such losses are avoidable. For example, Tokyo managed to reduce its freshwater leakage from 20% in 1955 to barely 2% today. Even cities that are much poorer than Hong Kong do better. Cambodia's capital Phnom Penh reduced its losses from 60% in 1998 to just 6% in 2008.

The enormous scale of water leakage is costing the city an estimated 1.35 billion Hong Kong dollars annually (US$173 million). It’s estimated that the Water Supplies Department (WSD), which overseas water supply and sanitation, lost nearly HKD 17 billion (US$2.1 billion) from 2004 to 2015 as a result.

“There is an illusion that Hong Kong has an infinite source of fresh water supply,” says Evan Auyang, chairman of environmental think-tank Civic Exchange, which has released a report on Hong Kong’s water woes titled The Illusion of Plenty. He blames the losses on low water tariffs, gaps in water agreements, and poor implementation of water conservation rules.

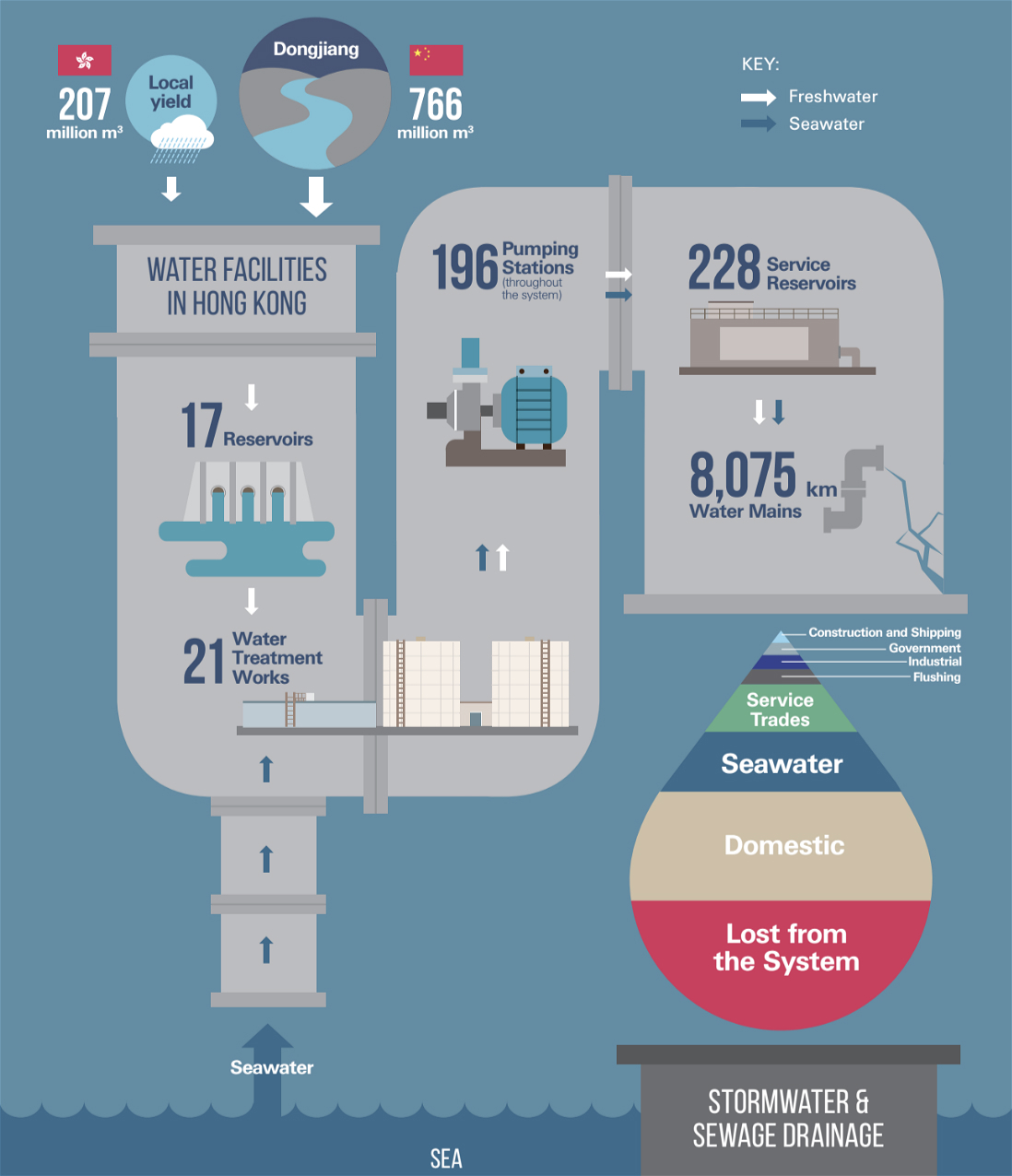

Generalised overview of Hong Kong's water supply

Whack-a-leak

Authorities in Hong Kong have been trying to fix the water problem for a while now. According to the Civic Exchange report, total water loss in Hong Kong was 26.5% in 2010, with losses from the government’s mains supply pipeline accounting for 20% of total production. Other causes of loss included illegal extraction, inaccurate metering and poorly maintained pipelines on private property.

To resolve the issue the WSD launched a programme to plug the city’s pipes, setting a target to reduce water loss from 20% to 15%. This effort was successful, with 91% of the mains network leakages repaired.

But in 2015, five years after the intense drive, fresh water loss actually increased from 26.5% to 33%.

While losses from the mains network declined to 15% of production, other categories spiked significantly. In particular, losses on private property increased more than five-fold to 14% of production.

Water guzzler

Each year Hong Kong consumes 1.25 billion m3 of water. This includes 820 million m3 of fresh water, with the remainder seawater. On average, per capita consumption of water in the city is 224 litres, of which 132 litres is freshwater and 92 litres is seawater.

Each year Hong Kong consumes 1.25 billion m3 of water. This includes 820 million m3 of fresh water, with the remainder seawater. On average, per capita consumption of water in the city is 224 litres, of which 132 litres is freshwater and 92 litres is seawater.

Taken alone, the per capita freshwater consumption is 21% higher than the global average. But when the use of seawater is included (Hong Kong is one of the few countries to use it for flushing toilets) consumption doubles to twice that of the global per capita average of 110 litres.

Other cities with similar freshwater constraints as Hong Kong use much less. Singapore has reduced per capita consumption from 170 litres a day in 1998 to 151 litres in 2015. Shanghai does even better at just 106 litres per day. In contrast, Hong Kong’s total consumption (freshwater and sea water combined) has grown by a quarter since 1998.

Take it or leave it agreement

As Hong Kong grew in the 1960s its water scarcity increased. In 1965, in a bid to resolve the problem, it struck a deal with China's mainland government. The DongShen Agreement resulted in the Dongjiang-Shenzhen Water Supply Project, which imported water to the city from the Dong Jiang River. The agreement, which is still in place also provides water to seven cities in China, including Shenzhen, Guangzhou, Huizhou and Dongguan.

To further streamline the water supply from Guangdong the DongShen Renovation Project was initiated at the cost of RMB 4.7 billion (US$680 million) in 1998. The Hong Kong government contributed nearly half the cost with 2.36 billion Hong Kong dollars (US$303 million).

“Such a massive investment itself speaks to Hong Kong’s massive reliance on Guangdong,” says Evan. Guangdong province today fulfils 65-90% of Hong Kong’s freshwater supply, with local resources contributing the rest.

But a year after the DongShen Renovation Project, the city’s Audit Commission pointed out that Hong Kong was being forced to take a full allocation of water irrespective of how much the city used. Hong Kong does not consume its entire 1.1 billion m3 allocation from Guangdong, typically consuming under 820 million m3 of Guangdong water. Between 2010 and 2012 the city utilised 73%, 89% and 76% of its allocation, respectively.

Hong Kong asked the Guangdong authorities to change the deal in 2014 so that payment would be made for actual supply only. But the Guangdong authorities made it clear that the existing deal guarantees Hong Kong at least 99% of its 1.1 billion m3 allocation, and changing the deal would mean the loss of that guarantee, with Dongjiang waters being allocated elsewhere.

Solutions

Fixing Hong Kong’s water problem will take more than plugging a few leaks.

For a start, the structure of the WSD means that many city departments must get involved before even simple repairs can be undertaken. The city’s development bureau is in the process of installing smart metres to check leakages and improve metering accuracy but with poor service and insufficient inspections from WSD, combined with ageing private housing – by 2047 nearly 326,000 private housing units will be over 70-years-old – the city faces an uphill struggle.

Hong Kong needs a multi-pronged approach to reducing water loss and consumption, according to Sam Inglis, an environment research analyst and one of the Civic Exchange report researchers. “One of the best approaches would be to shift from a complete engineering-based approach for water conservation to social awareness and a hike in the water tariff,” he says. The water tariff has not been revised since 1995.

Evan points out that the city must also look toward other sustainable sources of water, particularly as climate change may reduce river flows in the Pear River catchment, reducing the annual flow of the Dong Jiang River.

“We suggest that a circular water management system should be adopted,” says Evan, in which water is recycled for reuse by the city.

The potential pay-off is huge though. The report claims that if the city could save 24% of its water, reducing supply from the Dong Jiang River from 60-80% of supply to 40-60% by 2030.