At their summit this year in Hangzhou, G20 leaders have been tackling head-on the effects of a languishing and increasingly unequal global economy.

Encouraging more inclusive economic growth was high on their political agenda, perhaps because they understand its connection to the recent surge of anti-establishment politics around the world.

And for the first time, in what may prove to be a watershed moment, they also discussed how to “green” the financial system as part of supporting strong, sustainable and balanced growth. (Link to G20 leaders “Green Finance” communiqué.)

They were right to do so; risks to growth linked to environmental issues are becoming more complex and interconnected and more material to business. A key question is whether financial institutions are managing environmental risks appropriately? Can better analysis of these risks lead to a more efficient allocation of capital and drive the long-term stable and sustainable global growth that the G20 has aspired to?

This is not a hypothetical conversation. These types of challenges are already being faced and addressed by G20 countries. In recent years, Brazil has suffered its worst drought in decades. The majority of the country’s electricity comes from hydroelectric dams. Shifting to thermal power generation meant that electricity prices soared by up to 70%. Inflation followed, with implications across the Brazilian economy. Had the resulting change in market prices been priced into prior valuations by investors?

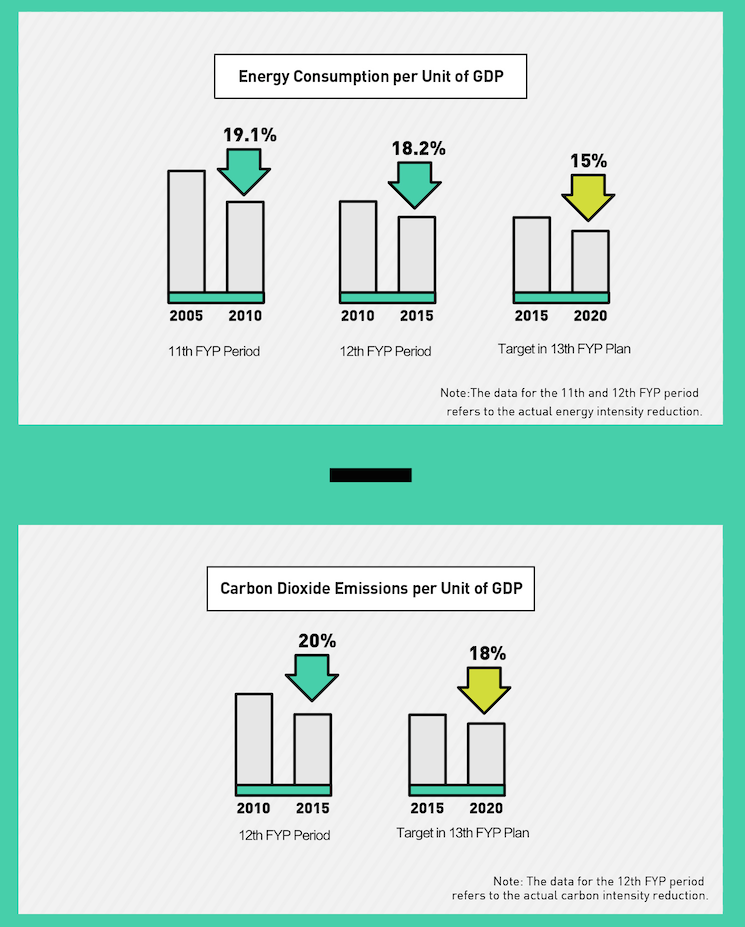

And in China, the latest Five-Year Plan has committed to continue to grow the Chinese economy while reducing its carbon intensity by 18% against 2015 levels (see graphic below).

One major driver for this move is the societal reaction against poor urban air quality, caused by heavy industry. Achieving this target will require significant shifts of capital to underpin the greening of the Chinese economy. Those caught behind the curve of this environmentally-inspired transition will face material risks.

In December 2015, under China’s leadership of the G20, the group created a Green Finance Study Group (GFSG). Its purpose is to identify what options exist for governments to catalyse the private sector to scale up green finance to the order of tens of trillions of dollars over the coming decade. Alone, China has said it needs around US$460 billion (3 trillion yuan) each year to finance its green investment programme.

Importantly, this work has not been led by environment ministers, but by finance ministers and Central Bank governors. Green finance now sits right at the heart of global economic decision-making.

The Cambridge Centre for Sustainable Finance, a research hub on financial market reform, hosted by the University of Cambridge Institute for Sustainability Leadership (CISL), has been formally involved as a Knowledge Partner since the launch of the GFSG.

As part of its work, the GFSG asked us to review current practice of financial institutions globally to understand the degree to which they are already innovating to integrate environmental risks into decision-making. This is critical because unless the institutions controlling so much of the world’s capital are fully sensitised to growing environmental risks, they won’t seek innovative solutions with the determination and focus that is so badly needed.

Our analysis has drawn three clear conclusions:

1. Important innovation is already happening in the financial sector, but it is at the margins of mainstream practice. For example, a Chinese commercial bank, ICBC, has conducted stress testing on the impact of air quality regulations on the credit risk of its heavy polluting clients, finding significant deteriorations. Elsewhere, UK-based insurers have quantified how extreme weather events can drive food price spikes and hit stock markets around the world.

2. There are real challenges to integrate such innovation into mainstream practice and therefore good reason for regulatory attention. The need to make good quality, relevant data available is well understood. Knowing how to process that data by connecting scenario analysis to financial impacts, however, requires multi-disciplinary expertise that is not often found within a single institution.

3. G20 Governments should put in place formal structures to accelerate action on environmental and financial risks across banking, investment and bond markets. Governments and regulators need to help build capacity in local markets, plug knowledge gaps, improve data and level the playing field. All of these sectors need to be ‘greened’ to achieve the mobilisation of tens of trillions of dollars of green finance

It will be important now to turn the recent momentum for green finance from the G20 Summit into concrete action. It will take everyone’s effort to make this happen, from central banks and investors to credit rating agencies and regulators. .

China’s own actions are a clear example of leadership, globally. For example, as G20 Leaders departed Hangzhou, the China Banking Regulatory Commission revealed separate work it has been doing with the Cambridge Institute for Sustainability Leadership to green the finance of China’s commodity imports.

In the foreword of the report, director Ye Yanfei says:

“The production and trade of agricultural commodities play an important role in generating carbon emissions and impacting sustainable development. China is one of the biggest importing countries of agricultural products.”

“Implementing green credit standards in trade finance processes for agricultural commodities is therefore an urgent task for China’s banking industry still to achieve.”

Across all sectors it seems the race is on to green the financial system.

See CISL’s report on Environmental risk analysis by financial institutions – a review of global practice.