Wildlife traffickers from a small, sleepy village in Vietnam are using Facebook to offload large amounts of illegal ivory, rhino horn and tiger parts, an investigation has revealed.

The results of an 18-month sting by the Wildlife Justice Commission (WJC) – shared with the Guardian – were presented at a public hearing in November at the Peace Palace in the Hague. They showed how social media sites such as Facebook are allowing traders greater access to customers.

“It’s wildlife trafficking on an industrial scale,” said Olivia Swaak-Goldman, the executive director of the WJC.

Undercover investigators visited the Vietnamese village of Nhi Khe, known as a wildlife trafficking hub, five times in the past year and scoured Facebook and WeChat, which is popular in China. In all, they tallied illegal wildlife products worth US$53.1 million (366.6 million yuan) stemming from just 51 traders in the village for sale in person and online.

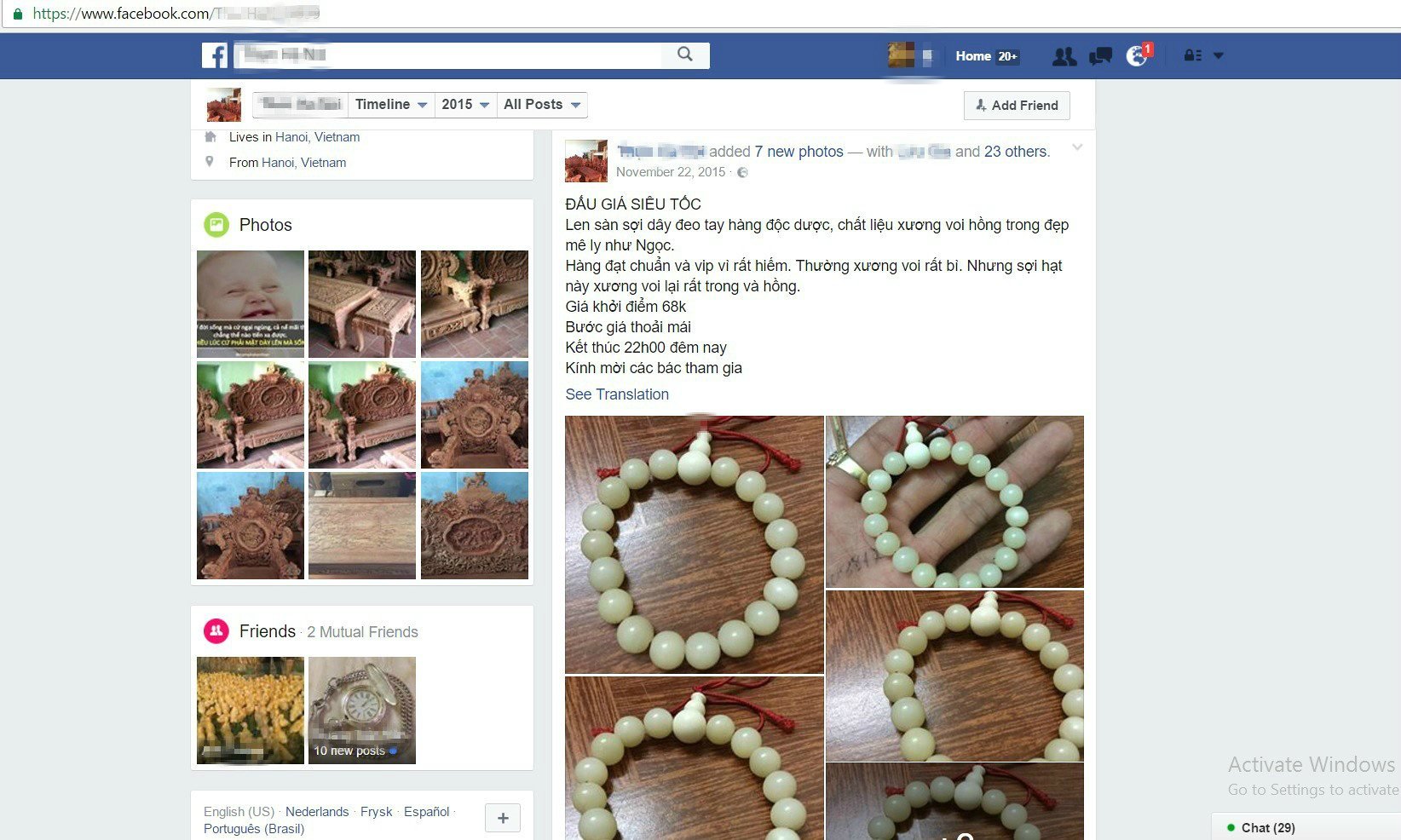

Nhi Khe traders are primarily using Facebook to sell processed ivory products. But even whole ivory tusks and tiger bone paste have been sold on the platform.

“Social media provides a shopfront to the world,” Swaak-Goldman said.

Items are being sold in closed or secret groups through auctions, which means new buyers or sellers have to be approved before being allowed into the group. Once in, traders will use instant messaging to keep in touch with buyers.

Such Facebook groups are also allowing traders to meet a wide array of potential new buyers. Payment is usually done via WeChat Wallet.

WJC investigators have found that Facebook is primarily used by traders to sell wares locally or across other parts of Southeast Asia. In contrast, traders use WeChat to sell unprocessed products in bulk to Chinese traders. Since Vietnamese traders aren’t able to write in Chinese, they tend to offer products on WeChat via voice message.

Also see: China’s deadline on ivory phase-out looms

Also see: China’s legal ivory trade is ‘dying’ as prices fall

A beaded elephant bone and ivory bracelet, advertised for sale on Facebook and identified by the WJC. Image: Wildlife Justice Commission

This appears to be a widening pattern for wildlife traffickers in the region. In March, Traffic, another anti-wildlife trade organisation, announced that Facebook had become a popular tool for selling both animals parts and live animals with wildlife traffickers in Malaysia. These traders also use auctions in closed and secret groups to keep their illegal activities out of the public eye.

The WJC approached Facebook about the issue and a spokesperson from the social media group told it: “Facebook does not allow the sale and trade of endangered animals and we will not hesitate to remove any content that violates our community standards when it is reported to us.”

The social media giant’s community standards “prohibit the use of Facebook to facilitate or organise criminal behaviour that causes physical harm to … animals”.

Swaak-Goldman said Facebook needs to go further, including shutting down traders accounts and cooperating with law enforcement.

Facebook has the capacity to delete posts or entire accounts, but the group said how it reacts depends on the severity of the breach in community standards. As to working with law enforcement, Facebook said it would not comment on specific legal cases.

Sales are also continuing in person in Nhi Khe, which is home to just a few thousand people. Historically, Nhi Khe was a village of wood carvers, but in recent decades its economy has shifted towards this more lucrative trade, dealing in everything from dead baby tigers in a jar to sawed-off rhino feet, as documented in photos and videos taken by WJC investigators. The village is perfectly situated for the illicit trade, being 20 kilometres south of Hanoi and not far from the Chinese border.

Throughout the investigation, the WJC tallied products representing up to 907 dead elephants and 225 dead tigers. Experts believe most of the tigers were born in tiger farms because if they were coming strictly from wild tigers, it would represent nearly 6% of the world’s population.

But even more surprising was the amount of rhino material passing through Nhi Khe. Investigators detailed rhino parts from 579 individual rhinos, nearly half of the total amount of rhinos killed in South Africa last year.

And these numbers don’t take into account products not directly seen by investigators either via social media or in person.

“Can you imagine what the real number is?” said Swaak-Goldman. “This is the tip of the iceberg.”

The WJC also noted products in Nhi Khe that were from bears, pangolins, hawksbill sea turtles and helmeted hornbills.

In October, WWF and the Zoological Society of London released an update of the Living Planet Report that found the world is suffering a catastrophic loss in global wildlife. According to the report, wildlife populations fell by 58% from 1970-2012 and we are on track to lose two-thirds of wildlife populations by 2020.

The global wildlife trade is playing a leading role in what could become the world’s sixth mass extinction event. The illicit trade is estimated to be worth around US$23bn (158 billion yuan), making it the fourth largest illegal trade after drugs, arms and human trafficking (and that’s not including illegal fisheries, worth between US$10 billion and US$23.5 billion annually).

Over the past year, Nhi Khe traders have stopped showing their products in windowed store fronts, but the trade remains brazenly open, even more so than online.

“On the front [of the shops], it advertises in Mandarin ‘rhino horn’, ‘tiger’, ‘ivory’. It’s like buying a Big Mac,” Swaak-Goldman said.

Ivory is in high demand worldwide for carvings and decorations, while rhino horn is believed, against all evidence, to be a curative in eastern Asian medicine. But Swaak-Goldman said tiger parts have largely become a status symbol for men. They are a part of the “Vietnamese gangster” look, she said, adding that wearing the body parts of a dead tiger is “a fashion statement with its claws and its slight hoodlumism”.

Such beliefs are killing off the world’s megafauna. Tigers are listed on the IUCN red list of endangered species. Several tiger subspecies are already extinct and all those remaining in Southeast Asia (Sumatran, Malayan and the Indochinese) are on the verge of extinction. Meanwhile, Africa has lost 110,000 elephants from 2007-15 due to an epidemic of poaching, potentially putting forest elephants – which have been harder hit than savannah elephants – at risk of annihilation.

A trader in Vietnam shows off his tiger claw necklace, gun and other spoils of the trade. Image: Wildlife Justice Commission

While the WJC is working with Facebook to combat the trade online, its biggest target is the Vietnamese government. The WJC began communicating with the government as soon as it launched the investigation in July 2015. Since then, it has handed over thousands of pages of evidence prepared by qualified law enforcement professionals to five government agencies.

“Unfortunately, we have not received an adequate response or seen indication of serious law enforcement activity. We have continued to offer our support and co-operation to dismantle this network,” Swaak-Goldman said. “Given this lack of action [by the government], we have no choice but to present this investigation at a public hearing.”

Experts have long viewed Vietnam as a hub for the global wildlife trade, especially in rhino horn. Today, three of the world’s five rhino species are listed as critically endangered by the IUCN red list, while the world is losing more than 1,000 white rhinos a year to poachers. Poaching has also taken a human toll: both wildlife rangers and poachers are sometimes killed in gunfights.

The WJC believes simply shutting down the trade in Nhi Khe alone could have a “significant impact” on global rhino poaching, given the staggering amount of product moving through the village.

If caught and convicted, illegal traders in wildlife products in Vietnam face up to three years in jail. But the sentence could jump to seven years if the trade is deemed organised, which the WJC asserts is the case in Nhi Khe. Still, this is lower than other crimes in Vietnam. For example, possessing heroin in the country can lead to a life sentence or the death penalty.

But Vietnam has shown some signs of creating a new strategy on wildlife trafficking. In September, Prime Minister Nguyen Xuan Phuc issued a directive urging local and regional officials to step up the fight against wildlife trafficking. The country has also announced a partnership with the US to combat the global trade. Vietnam organised a major international conference on the global wildlife trade in November.

Although only a year old, the WJC has already had success combating the illegal wildlife trade: an investigation resulted in the arrest of 16 wildlife traders in Malaysia in September.

This article is republished with permission from The Guardian