“The Arctic permafrost is melting, possibly releasing giant viruses! We might live to see the extinction of the polar bear!”

The long, hot summer of 2018 has been the source of much viral content and online discussions in China over the last few months.

But the connection between sustained hot periods and climate change is often missed. Anyone who works in climate change communications knows that the climate is a hard sell. This is understandable; the science is hard and the various negotiations are not much simpler. Getting people to notice, care and talk about climate change has always been a problem, particularly in China where climate change action comes mostly from state level.

So how can we make the most of an opportunity where hot weather turns global warming into a hot topic?

Hotter than average discussions

Hot temperatures often make the news over the summer months, but this felt like the first year that talk about such temperatures turned into concrete concerns about global warming.

This perhaps can all be attributed to August’s global heatwave. From Scandinavia to Japan, the world baked – and media outlets worldwide discussed the record temperatures in a global context. On 4 August, Chinanews.com ran an article about the heatwave in Europe and the 32 degrees Celsius temperatures being recorded above the Arctic circle. At the same time, Xinhua reported on forest fires in Greece and fish die-offs caused by the high temperatures.

China also saw longer-lasting summer heat than usual. As of August 15, the National Meteorological Centre had posted amber high temperature warnings for 33 consecutive days – meaning three or more days of temperatures topping 35 degrees Celsius. The constant heat and humidity led people to wonder if this, perhaps, is the new normal.

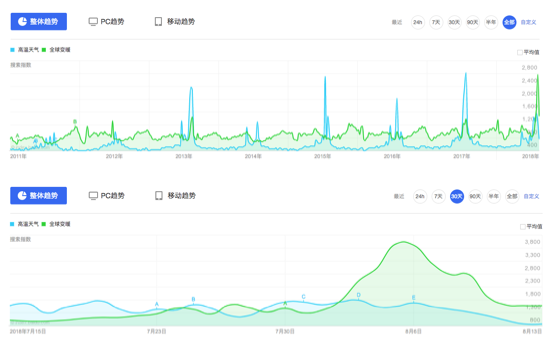

And internet browsing data shows the extent of people’s interest. The phrase “global warming” was searched for much more often on Baidu, China’s most popular search engine, than in the previous seven summers, and even more than the phrase “hot weather”.

Graphs of search term use from Baidu. The blue line indicates searches for “hot weather”, and the green line shows searches for “global warming”. The top graph covers the last seven years, and the lower graph shows the last two months. Image: index.baidu.com

Extreme weather events linked to climate change

Advances in climate modelling in recent years have made it easier for the public to accept the link between extreme weather and climate change. When extreme weather occurs, scientists can use these models to simulate both the actual world, and a world where no greenhouse gases have been released by human activity. Using these two models, they can determine to what extent climate change has contributed to extreme weather events.

For example, precipitation from Hurricane Harvey in 2017 increased threefold due to climate change, while the US heat wave in February of that year was made three times more likely due to climate change. Human activity also makes events like the 2013 heatwave on China’s east coast 60 times more likely than in the 1950s, according to research by China’s National Climate Centre.

As traditional climate messaging faces challenges from sceptics, communicators will often avoid linking any one extreme weather event to climate change. But as research into extreme event attribution progresses, these cases are now ideal opportunities to put forth the climate message.

And there is plenty of research to show that high temperatures make people more inclined to believe in climate change. Data gathered from 89 countries shows that when temperatures are above the seasonal average, acceptance of climate change increases.

Time to talk adaptation

Discussions on adapting to climate change are becoming more pressing. With worsening extreme weather events, the public needs to understand the importance of preparing and adapting, and climate communicators need to work out how to convert this renewed awareness of climate change into real behaviour change.

Recognising the link between extreme weather events and climate change doesn’t necessarily change behaviours, but public action on climate change – such as reducing meat consumption and choosing low-carbon transportation – could reduce temperature rises in the year 2100 by as much as 1.5C, according to one model.

So when the heatwaves strike again, climate communicators can’t just talk about climate change alone; we need to get people to look at their lifestyles and remind them to prepare for even worse weather.

And at the social level, we need to avoid the focus on mitigation and emphasise the urgency of adaptation to policy-makers and businesses – only pro-active investment in long-term adaptation measures will prevent us from paying a higher price later on.