China’s economic planning department has recently approved a flurry of new rail projects at a scale that Green New Deal advocates in the United States would envy. A total of 800 billion yuan (US$120 billion) will be poured into rail construction in 2019 as part of a plan to stimulate the domestic economy.

These investments are the latest in a decade-long building spree that has rapidly outfitted China with the world’s most extensive high-speed rail network – larger than all others combined.

Trains are among the most energy-efficient modes of transport, so new lines could be a major asset to China’s decarbonisation. However, studies show that some of China’s high-speed lines have relatively large carbon footprints and are chronically underutilised. As China continues to pump money into an ever-expanding rail empire, these projects tell a cautionary tale.

Infrastructure boom

Little more than a decade ago, it took 12 hours to travel between Beijing and Shanghai by train. Now it takes four and a half. China’s 13th Five-Year Plan (2016-2020) seeks to replicate that feat, setting a target to build 30,000 kilometres of high-speed rail connecting 80% of the country’s major cities.

The recently announced high-speed rail projects span China. They will connect the Guangxi gulf economic zone, historical Xi’an and Yan’an, and cities along the Yangtze River in Jiangsu province.

In recent years, construction – particularly the production of steel and cement – has been driving the increase in China’s energy consumption. In February, the government reported that China’s coal consumption increased in 2018 for the second year in a row, with carbon dioxide emissions following suit.

Zhang Baotong, the director of a Shaanxi economic research institute, acknowledged the thirst for materials of the projects recently invested in. Zhang said building subway systems not only meets public demand but can also absorb overcapacity in steel, cement and other industries, thereby boosting the economy.

From a climate change mitigation perspective, the emissions intensity of these construction materials raises a key question. Are train trips energy efficient enough to offset emissions produced by crisscrossing the country with thousands of kilometres of new tracks?

Does high-speed rail lower emissions?

Globally, high-speed is recognised as a part of the transition to a low-carbon future. In a recent report, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change called for its construction to help phase out flights.

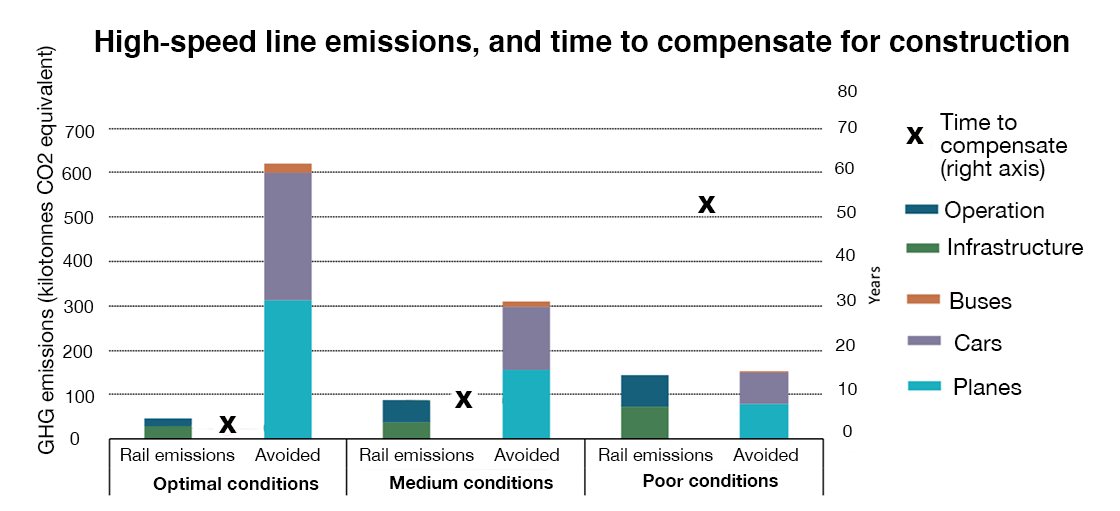

However, building a high-speed line does not guarantee significant emissions savings. The Future of Rail, a new study from the International Energy Agency (IEA), demonstrates why.

A few factors determine a high-speed line’s carbon footprint. First, such lines typically flourish at distances between 300 and 1,000 kilometres, connecting cities where residents are relatively affluent and in the habit of intercity travel. In order to lower emissions, they must be efficient to construct. The trains they carry need to be powered by a green electricity grid, to run frequently and near capacity, attract people away from other higher-emissions modes of travel, like planes and cars, and not generate too much new demand for travel.

Under optimal conditions, a line between major cities like London and Paris can decrease emissions almost immediately, IEA’s model shows. However, under suboptimal conditions, the project might only slightly reduce emissions and those benefits could take over 50 years to materialise.

Source: IEA

Source: IEA

Beijing to Shanghai in 4.5 hours

Where does China’s rail network fall on this spectrum? An academic study of the lifecycle emissions of a key high-speed rail line in China provides some clues.

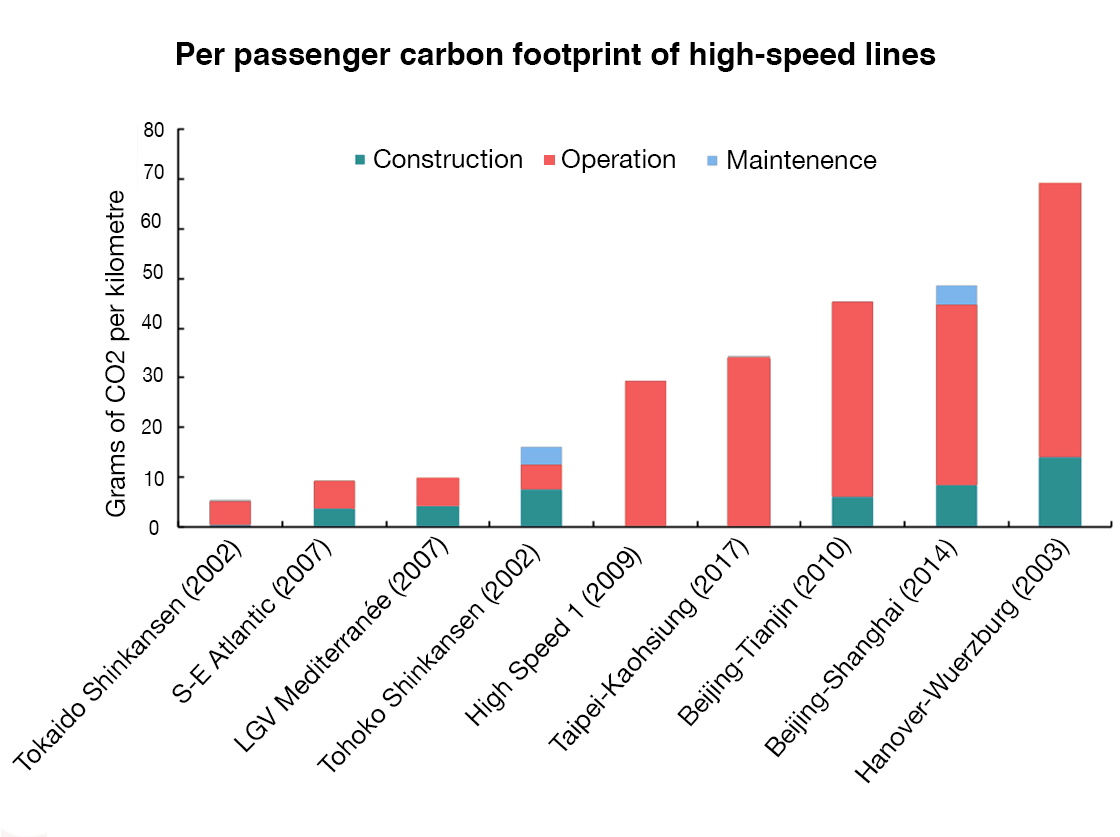

Researchers from the Chinese Academy of Sciences and other institutions analysed the Beijing-Shanghai high-speed line, which is China’s most highly trafficked. They found its carbon footprint to be much higher than high-speed railways in other countries. This is largely due to the dominant use of coal for electricity generation in China. However, the authors’ analysis suggests that the line actually has strong potential to fulfil many of the IEA’s criteria for a low-carbon line.

Source: Chinese Academy of Science and Xiamen University

Source: Chinese Academy of Science and Xiamen University

According to the research, operating the line accounts for 70% of its emissions, while construction only accounts for 20%. As China continues to add more renewable energy to the grid this will be less of an issue. That is one of the key climate benefits of electric rail compared to oil-fuelled cars and planes.

The study also found that the number of passengers on the train increased during the analysed period from 2011, when the train opened, to 2014, meaning the per passenger carbon footprint fell. This may be a common phenomenon in China, Jacob Teter, an energy policy analyst at the IEA suggests. Due to the rapid nature of the rail buildout, it may take years for the trains to reach full capacity.

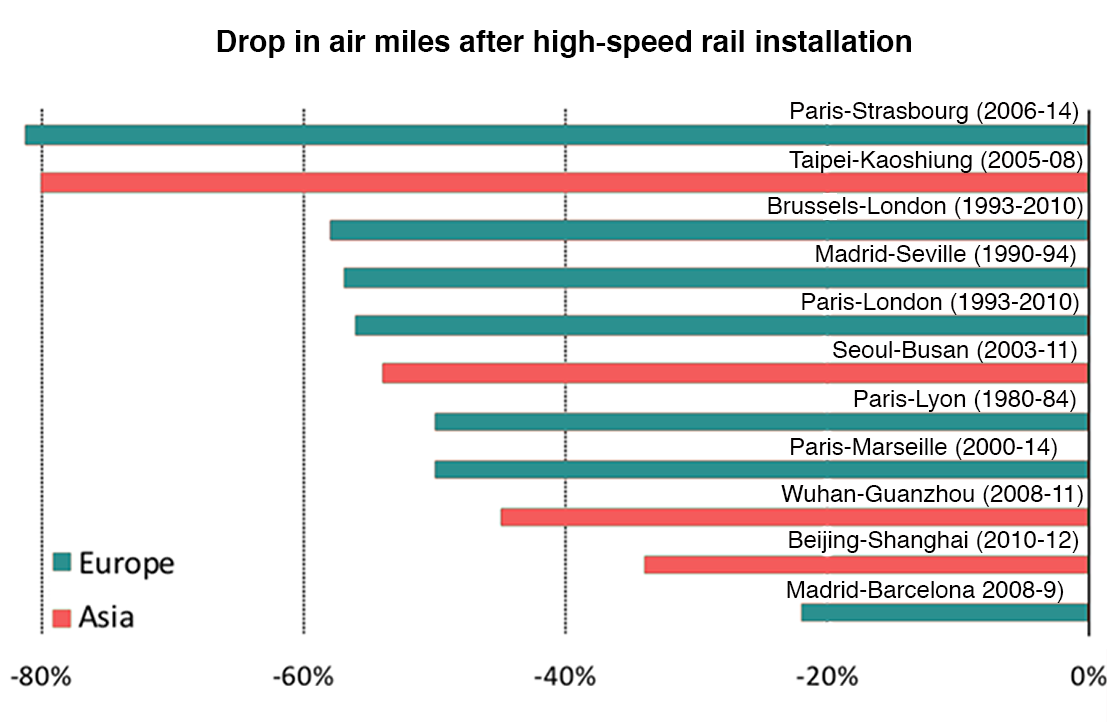

Importantly, the IEA study also shows that the Beijing-Shanghai line has managed to shift travellers away from flying, a key factor in reducing emissions.

Source: IEA; Chart: chinadialogue; Please note the varying time periods

Source: IEA; Chart: chinadialogue; Please note the varying time periods

The white elephant problem

Far from the densely urbanized corridor between Shanghai and Beijing, high-speed rail projects in sparsely populated regions of western and northern China are more tales of caution than low-carbon success.

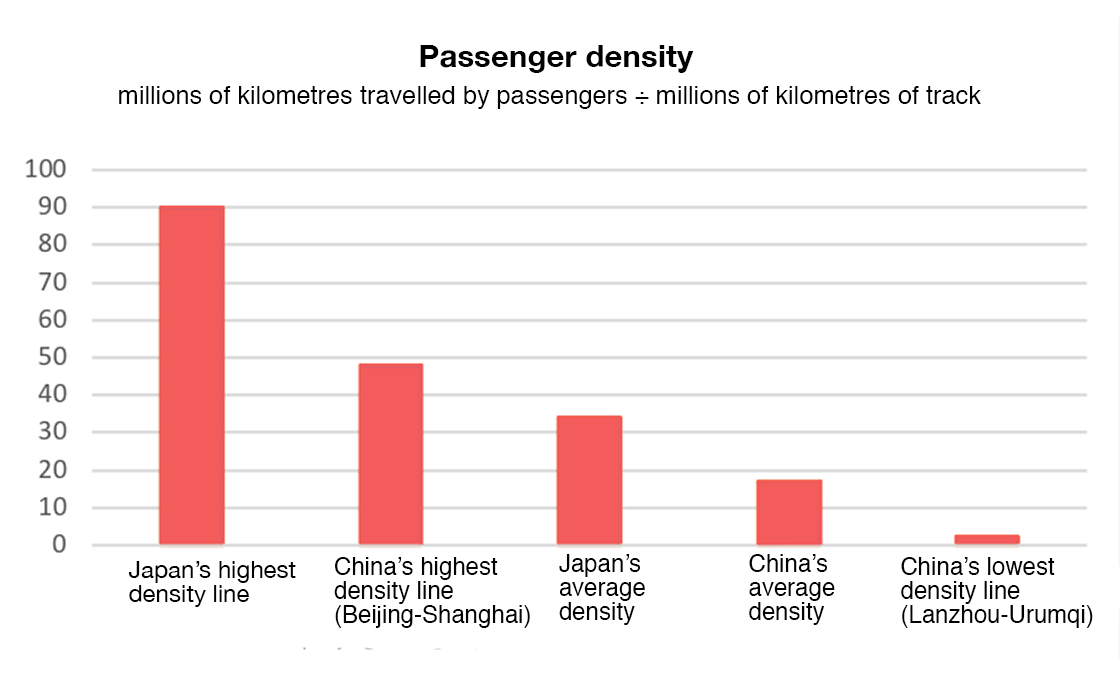

In a January Caixin op-ed, Beijing Transportation University professor Zhao Jian wrote that China’s high-speed lines, besides the Beijing-Shanghai and Beijing-Guangzhou routes, are largely underutilised. By comparison, Japan’s average high-speed rail utilisation rate is twice that of China’s, he wrote. IEA’s study also shows that the number of trains China runs on its high-speed tracks is almost half that of Europe and Korea, and lower than the global average.

Data source: Zhao Jian (Caixin); Chart: chinadialogue

A debt-fuelled infrastructure construction model has led to the development of ghost cities in China; it can also create perverse incentives for irrational high-speed rail development, according to Zhao Jian.

In a January Weibo post, well-known blogger “Beijing Saidong” criticised the funding of expensive high-speed rail projects in provinces with dwindling populations like Heilongjiang, the province in the far northeast bordering Russia. The blogger argued that resources would be best allocated to cities with expanding populations.

Data shows that sparsely populated western provinces have received a disproportionate level of rail and highway investment per capita. China’s least trafficked high-speed route is the 12-hour ride from Lanzhou to Urumqi in China’s far west.

As new megaprojects are built, sometimes between cities that do not have sufficient travel demand, high-speed rail’s less glamorous cousin, freight rail, has been neglected. Only 17% of freight moves by rail now whereas 50% did in 2005. The increase in trucking has led to worsening air pollution and increased emissions in this sector. According to IEA, the emissions-intensity of freight rail is nearly ten times lower than trucks.

Through the latest national clean air action plan (2018-2020), the central government is trying to rectify this underinvestment by setting higher targets for freight by rail.

Commenting on this imbalance in an interview with chinadialogue, Zhao said, “At present, I don’t think any more [high-speed rail] should be built … What should be built now is conventional [passenger and freight] rail. It has a lot of space for growth.”

Low-carbon ticket?

The IEA’s most ambitious rail scenario for 2050 projects that China could decrease its transport emissions 12% by continuing to massively expand rail, including reaching over 100,000 kilometres of high-speed track. China’s approach could be a model for a world looking to decarbonise its transportation system.

But as the country aims to reach a total of 38,000 kilometres of high-speed rail by 2025, climate advocates remain watchful.

Lauri Myllyvirta, a senior air pollution analyst at Greenpeace, said, “China’s major dilemma is that investment of all kinds is driven more by the perceived need to maintain artificially high levels of GDP growth and demand for energy-intensive commodities, rather than an actual need for the things being built. That doesn’t mean all projects are poorly conceived of course, but it does increase the risk.”