Pollution is often as rife in rural China as in its urban industrial heartlands. In some cases, mining companies ride roughshod over environmental laws; and cottage industries dismantling electronic waste create their own health hazards. So what recourse do such communities have? Or must they make do with home-grown coping strategies to minimise the risks?

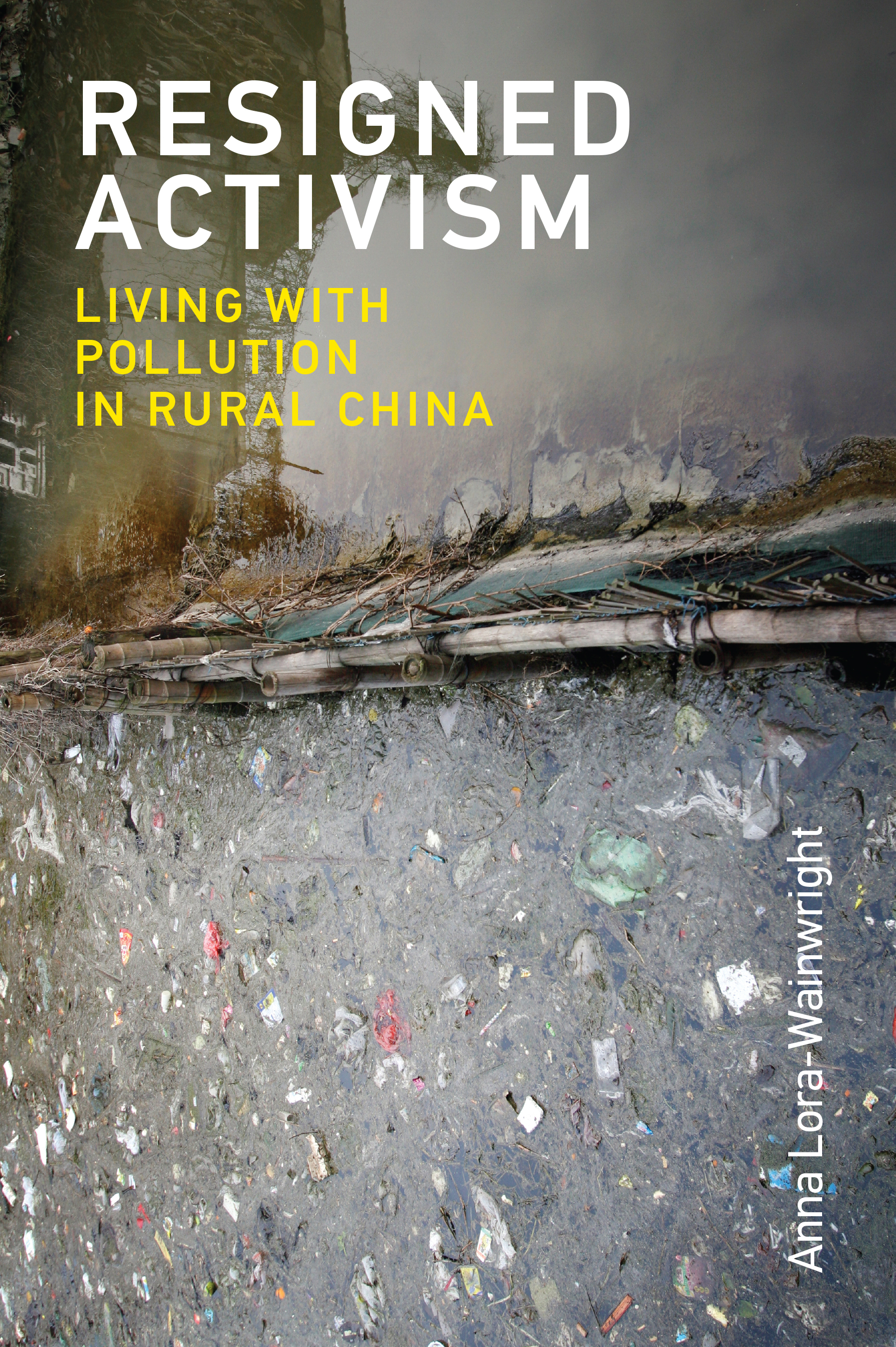

Anthropologist Anna Lora-Wainwright has spent years investigating these dilemmas. In her new book, Resigned Activism: Living with Pollution in Rural China, she argues that people who live with blighted landscapes deserve more attention in the study of environmental activism. She tells Fred Pearce why.

Fred Pearce (FP): "Resigned activism" sounds like an oxymoron. What do you mean by it, and why do you find it apposite for responses to pollution in rural China?

Fred Pearce (FP): "Resigned activism" sounds like an oxymoron. What do you mean by it, and why do you find it apposite for responses to pollution in rural China?

Anna Lora-Wainwright (ALW): I chose this term to highlight the complex nature of environmentalism in rural China. Studies of responses to pollution and other environmental threats tend to focus on activist movements. Less attention is given to individual responses – to fatalism, resignation and how pollution is naturalised. But if we want to understand environmentalism, we also need to understand these processes.

“Resigned activism” describes the small steps individuals and families take to minimise pollution’s effects physically, psychologically and socially, in circumstances where more classic forms of collective action may be unavailable or ineffective. These more individualised tactics include wearing masks, purchasing bottled water, closing windows at night to keep out fumes, avoiding the harmful jobs, and sending small children and pregnant women to live elsewhere.

FP: How is pollution naturalised? You talk in the book about people having a sense of a "local biology" and altering their sense of what being healthy means.

ALW: In all three sites where I worked, locals adjusted their expectations about what counts as a healthy body to accommodate local pollution. In Baocun – a Yunnan village surrounded by phosphorus mining and fertiliser plants – nose and throat infections, hand and feet swelling, and joint pain (possibly the early stages of fluorosis) were regarded as normal. When we asked them about their health, villagers almost always neglected to mention such conditions. They often said that the body can “get used to pollution”.

FP: You say at one point that you and your researchers experienced some of the health effects of serious local pollution. Can you give some examples?

ALW: This was particularly the case in Baocun. During fieldwork, I experienced headaches, sore throat and some nose bleeding, probably due to local pollution. In Guiyu in Guangdong, a hotspot for trading and processing electronic waste, I also suffered stinging eyes and headaches when I was in areas where plastics were burnt. The smell was sometimes overpowering.

FP: Is the attitude of people in Guiyu, where the pollution comes from local household enterprises, different from that in places where the pollution was imposed on them?

ALW: Yes and no. On the surface, it may seem that people in places like Guiyu are fully complicit. But communities are always more complex and stratified – costs and benefits are unevenly distributed. Migrant workers who make up the bulk of the workforce in Guiyu earn relatively little and are exposed to the worst risks.

FP: How honest do you think people were in their answers to your questions, for instance when local officials were present?

ALW: When officials were around, our interlocutors were certainly more cautious about suggesting that pollution affected their environment and their bodies. When they were alone with us, they sometimes went to the other extreme, to draw attention to their suffering. Some asked us to help them in obtaining redress from higher levels of government. And I can understand and sympathise with them for trying. We noticed this difference especially in our third study area, Qiancun, a heavily polluted lead and zinc mining village in western Hunan.

FP: What is the politics of pollution in China? Has the attitude of the centre to local pollution changed under Xi Jinping?

ALW: Under Xi, we have witnessed increasing efforts by the central leadership to show a strong commitment to curbing pollution. Xi has spoken of waging “war on pollution”, and there have been high-profile campaigns against air pollution, for instance in the steel-producing province of Hebei. But problems in many areas remain under the radar. Ultimately, poorer often rural localities are more likely to accept polluting firms in exchange for tax revenue and employment. These dynamics are unlikely to change in a hurry.

FP: Do local officials enforce environmental regulations adequately in rural China?

ALW: It’s almost impossible to generalise, because of both the huge variety of pollution and different local political economies. But from my own fieldwork and from a close reading of the excellent work of Chen Ajiang of Hohai University on “cancer villages”, enforcement is still a huge issue. Regulations have improved, but economic incentives to accept polluting activities in poor areas are still strong.

FP: It has been said that environmentalism is a form of politics that is sometimes tolerated more in China than other forms of activism, because the centre sees it as a means of calling local officials to account. Do you agree with that?

ALW: Critiquing misconduct among local, small firms is acceptable to higher levels of government, and can serve as a safety valve. The Chinese state is a complex machine ultimately geared towards self-preservation. Local polluting firms and low-level environmental protection officials are easy targets in the vital work of maintaining political stability. But often the line between this and flagging up systemic problems becomes blurred, and then tolerance towards citizens’ criticism quickly dissipates.

FP: Do environmental concerns remain a broadly urban and middle class concern in China? Or does your analysis of "resigned activism" reveal other aspects?

ALW: As an anthropologist, I have spent years sharing my life with Chinese villagers. So I feel strongly about showing that environmental concerns and awareness of pollution are not solely the domain of urban middle classes. Of course, the ability of poorer people to oppose pollution or protect themselves from exposure is much more limited. Often, they have internalised their lack of power to affect change. But to ignore the ways in which they try to counter pollution would inflict a further injustice on them and deny them the agency they do have.

FP: You say in the book's introduction that your work has "broader conceptual implications for the study of environmentalism". What do you have in mind?

ALW: It draws attention to less visible responses to environmental awareness. For cosmopolitan green campaigners, buying water bottles, wearing masks and protecting children may not count as activism. But such actions deserve attention. Where the openings for civil society activism are narrow, they may be the only actions people can take against pollution. To understand activism, I believe we also need to understand acquiescence.

Resigned Activism: Living with Pollution in Rural China by Anna Lora-Wainwright, MIT Press.